We all love to assemble lists of the best this and the most impressive that, the masterpieces of science fiction…but what about those books to which one returns despite flaws that are undeniable? I expect all readers have their own lists of flawed or problematic personal faves. Here are ten of mine.

This is in no sense a comprehensive list.

Rocketship Galileo was Robert A. Heinlein’s first juvenile and it shows. RAH was still working out how to write a compelling long narrative (he already knew how to write fine short stories). Rocketship Galileo, in which plucky engineer Don Cargreaves, his teen nephew Ross, and Ross’ pals Art and Maurice head off on the first trip to the Moon, features characters thin as typing paper. The science and tech were long ago superseded by history. Still, to quote an old review of mine: “if it’s wrong for an atomic scientist and three expendable teens to head to the Moon in a homemade rocket to shoot space Nazis, then I don’t want to be right.”

In Frederik Pohl and Jack Williamson’s The Reefs of Space, hapless political prisoner Steve Ryland is the chosen tool by which the autocratic Plan of Man (which already controls the Solar System) plans to extend its control to the Reefs of Space. The Plan has captured a jetling; an alien beast that uses an inexplicable jetless drive to flit between the worldlets of the reefs. Can Steve learn the secrets of the jetling? The novel (and its sequels) are extraordinarily pulpish, providing little hint that this book was published in the 1960s and not, say, a generation earlier. Still, the super-science Reefs, living fusion reactors, jetless drives, and an archipelago of force-field wrapped garden worldlets delighted me at the time, and still do.

Beckie Chambers’ Record of a Spaceborn Few has a problem shared by all of Chamber’s space opera (The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, A Closed and Common Orbit, and Record of a Spaceborn Few). From time to time the author commits scientific flubs so egregious that I would weep tears of blood while reading were that physiologically possible. Take, for example, the energy sources for one of her interstellar vessels:

When the Exodans first left Earth, they burned chemical fuels to get going, just to tide them over until enough kinetic energy had been generated through the floors.

[groan of despair, accompanied by helpless hand gestures] But such flubs are passing moments in books that otherwise please—full of engaging characters and homey worldbuilding. A determined reader can ignore the foot-powered starships and focus on the other stuff. Or so I tell myself.

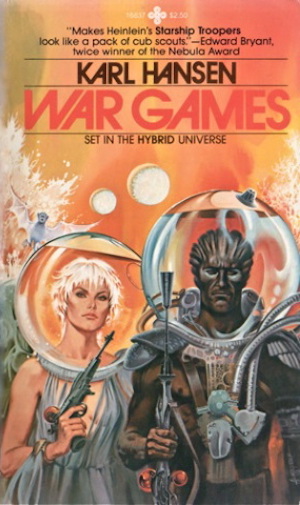

Karl Hansen’s 1981 War Games was the first book in the Hybrid series. Advanced technology allows humans to create bespoke ecosystems on various moons and planets, When that doesn’t work, they change themselves with bodymods. Sound like utopia? It isn’t. The Solar System has been turned into a nasty dystopia. Disgraced aristocrat Marc Detrs spends the novel in an increasingly self-destructive quest to avoid the doom seen in a prophetic vision. I’ve never seen a description of this novel more apt than Paul Knorr’s

“It’s about soldiers,” he said. “They fight, then they have sex, then they do drugs, then they fight some more.”

I do not have space to list all the ways in which this novel is problematic (although the fact that these people seem to have discovered every form of sex except consensual is a major one). It’s just that I have a weakness for thrilling tales of ecopoesis, terraforming, and pantropy, so despite all the eyebrow-raising stuff in the book, I keep returning to it.

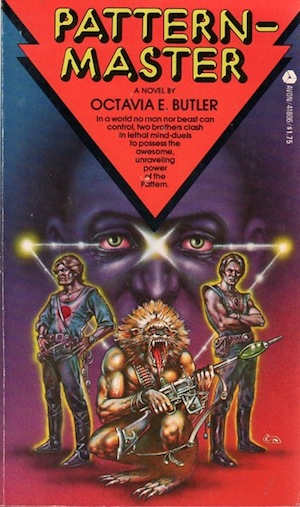

Although Octavia E. Butler’s Patternmaster was not her worst book (that would be Survivor), her tale of bitter dynastic struggle between members of a psychic aristocracy certainly wasn’t her best. The problems: protagonist Teray is the least interesting character in the book, and the book lacks much empathy for the characters. But even a sub-par Butler novel is a treat, and I reread Patternmaster from time to time.

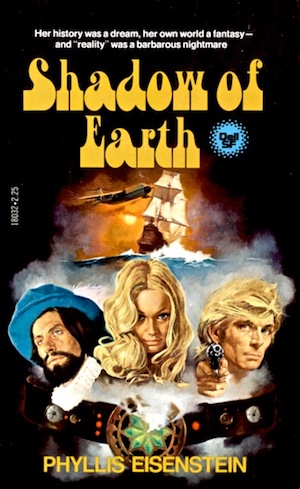

In Phyllis Eisenstein’s Shadow of Earth, Celia Ward, a Midwestern grad student/Spanish tutor, is taken to a parallel world by her lover. She expects a wonderful adventure. Instead, she’s betrayed: her lover sells her to a lordling who covets her blond hair and white skin. She’s to be a brood mare. Celia spends the rest of the novel trying to escape her new owner and his backward world. OK, so the worldbuilding here is implausible. It’s Celia’s struggle to regain her freedom that brings me back to the book.

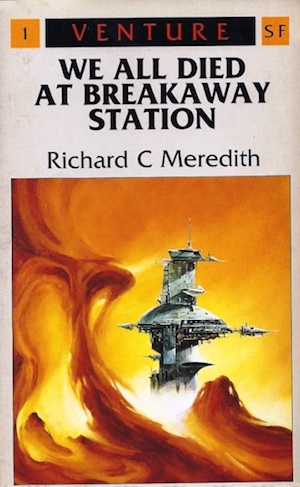

The eponymous station in Richard C. Meredith’s We All Died At Breakaway Station is a vital link in humanity’s communications network. It’s the facility through which hard-won information about the genocidal alien Jillies must pass. Therefore, the Jillies plan to destroy it. Absalom Bracer’s convoy is determined to defend it, despite the notable disadvantage that said convoy consists of a hospital ship and two escorts crewed by the walking wounded. The prose goes beyond purple into ultraviolet, but the novel delivers on its title with grand explosions and heroic sacrifices.

The Godwhale is one of just two novels by “T. J. Bass” (better known as Dr. Thomas Bassler). Having survived accidental bisection, Larry Deever is placed in suspension to await the day when technology can repair him. Two millennia later, he wakes into the Hive, a society with three trillion malnourished humans. The artificial intelligences that run the Earth have optimized for total numbers rather than quality of life. It is a world with no place for Larry and yet he is unwilling to be hounded into suicide. It’s not a good novel. The characters are thin when they’re not implausible (the handful of low-tech outcasts talk like second-year medical students). Still, it’s a vivid attempt to imagine how a world with trillions of humans might work (for dystopian values of “work”).

Andre Norton’s Galactic Derelict is the second in her Time Traders series. Native American Travis Fox is drafted into Operation Retrograde after he stumbles over the top-secret operation. In short order he and his companions are trapped on a functioning alien spacecraft whose navigation tapes are millennia out of date. The book is a product of a very different era. The prose is stilted, women are absent, the book is short and lacks depth. But it’s the first book I read that had travelers exploring the universe using unfamiliar alien technology—a well-worn trope today, but new to me when Norton first used it. This was also the first Norton I ever encountered, so I will always read it fondly.

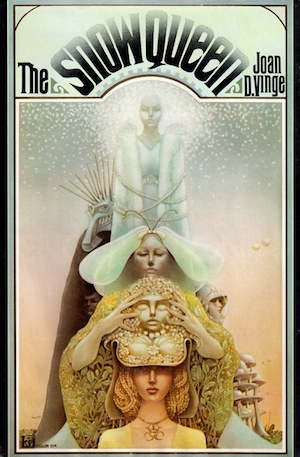

You might gasp to see Joan D. Vinge’s The Snow Queen on this list. After all, it won the Hugo and I’ve recommended it numerous times. How could I regard it as a flawed book? It’s because of Sparks, Moon’s lover. Moon, the protagonist, spends much of the book trying to recover Sparks from Snow Queen Arienrhod. Yet it’s never clear why Moon loves Sparks. We’re given many reasons to believe he’s a worthless cad. (Obviously people wouldn’t fall for the wrong people; imagine the misery if they did…) Still, SF plots wouldn’t work without the one impossible idea and in this case, it’s impossible to believe in Moon’s passion. It’s more as if she’s doing what she does because the plot requires it. That flaw aside, The Snow Queen’s many strengths—the prose, the plotting, the fact that Snow Queen Arienrhod has damn good reasons to do what she does—more than make up for the fact that had Moon been even half sensible, she’d have drowned Sparks before the plot even started.

Plus, the book had a cracking cover by the Dillons. You don’t want to know how many books I picked up on the basis of a Dillon, or a Whelan, or a Berkey cover…

These are some of my flawed favourites. What are yours?

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a finalist for the 2019 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, and is surprisingly flammable.